Home > Oasis of Peace > Community > Founder - Bruno Hussar > My Bruno

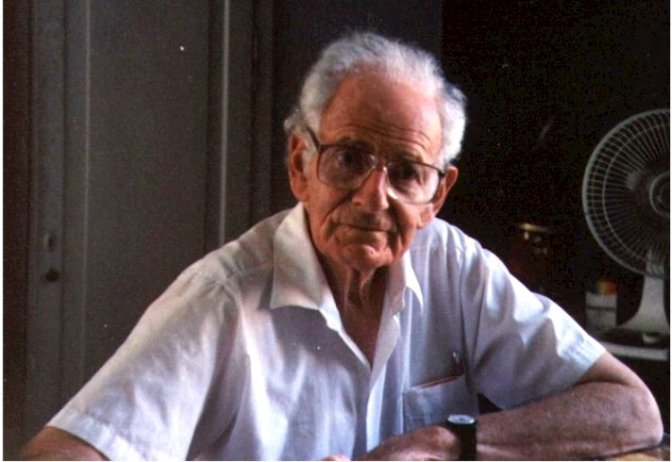

My Bruno

Tuesday 2 December 2008, by

I first met Bruno in a dialogue encounter session for Jewish and Arab students, at the home of Reuven Moscovitz, a teacher who had joined the group. This was in Rehovot, south of Tel Aviv.

At Reuven’s invitation, Bruno came to the meeting with Anne Le Meignen, to explain his idea about founding a Jewish-Arab community called Neve Shalom, and to recruit more people to join the project. The whole thing felt very strange to me. Bruno’s ideas were not very clear. They lacked a practical foundation. There was no clear work plan of the kind we are usually have in political work. He talked very generally about values and the entire idea was somewhat vague.

At the end of the meeting, Bruno invited everyone to come and visit him. At that time, our group was talking about setting up a joint Jewish-Arab school. Bruno annoyed us when he claimed that our idea wasn’t practical, because we were thinking of creating this school in one of the mixed cities, Akko or Yaffa or Haifa. In HIS community, he said, the idea would work!

After Bruno and Anne left and the group discussed all this, the general opinion was that they were rather naïve. But Reuven encouraged us to accept the invitation to visit them. "We’ll go visit there, and then we’ll deal with practical questions and with the ideas, too," he suggested.

* * *

At that same meeting, Reuven set a date for our visit and undertook to coordinate it with Bruno. When the day came, I tried to get there on my own from Rehovot but I couldn’t find the place they had talked about. "Why didn’t you come yesterday?" asked Reuven the next day. I explained that I had come to Latrun and continued as far as Shaar Hagai: "I didn’t find any village and I didn’t find any oasis," I told him. "What village? What oasis?" he said. "All they have there is an old bus and a pergola made of bamboo," he told me.

The next time, I went with Reuven himself. We got to the hill and met Bruno there, sitting under the pergola. He greeted us with a wide smile. He was waiting for another few people who had told him they were coming. We sat on some stones arranged in a circle there, and the new arrivals joined us. Bruno explained his idea some more, and we asked questions, which I saw that Bruno was in no hurry to answer. Sometimes he would toss a question back at someone, asking, "What do you mean by that?" In that way, we found ourselves broadening the discussion bit by bit. When I persisted in asking a question, he would say: "My answer to that is not important. I’m interested in hearing what YOU think about that."

* * *

Sundown approached, and the panorama was astoundingly beautiful. Bruno explained that whenever he was on the hill, he invited those with him to contemplate the sunset in silence. When he invited people who were interested in his idea to a meeting on the hill, he always made sure they saw a sunset.

Earlier during our discussion that day, I reminded Bruno that at our first meeting at Reuven’s house in Rehovot, when he explained about the village he was planning, he described children playing together, running all over the hill, climbing trees – an idyllic village somewhere. So where was it? Bruno laughed and said, "If you come and live here, all of that will happen."

Then, a few minutes before sunset, Bruno turned around to sit facing westward, and stopped speaking. Clearly he was inviting us to do likewise. There were a few clouds in the sky that hid the sun periodically as it set, until it finally disappeared from view. The sky began turning a deep pink. A few minutes later, we stood up and said goodbye to Bruno so that we could walk down the hill to the bus stop before complete darkness descended.

* * *

Evidently my first visit to the hill, and my meeting there with Bruno, had a very strong impact on me. I did not realize this at the time. Gradually I have come to understand that those meetings were a turning point in my life. Like any other young person nearing the end of his or her academic studies, I had dreams and plans for the future, mainly about going back to the village where I grew up, finding a suitable job, building a house, starting a family, and participating in the leadership of the village. All that was expected of me by the village residents, especially my parents, who were always talking about how those who went out to study at a university were expected to come back and contribute to the development of the village and help improve people’s lives there.

I had other dreams – my own private ones. These went beyond the level of being responsive to what was asked of me by the community where I was born and raised, and fulfilling my parents’ hopes for and expectations of me. My parents, like all parents, were concerned about my future, and they wanted me to be nearby, close to them. From earliest childhood, however, I had always tended not to follow the path more traveled, but to try a different way, something new. When I met Bruno, he reinforced this tendency in me. I saw in his ideas a host of challenges that matched who I was – someone looking for an alternative to the received wisdom and the usual path. I did not return to the village, causing some disappointment among all my acquaintances there. What I minded more was disappointing my parents.

I followed Bruno because he provided more substance and meaning for my dreams. The dream of becoming a success in the eyes of the society in which I had grown up, and the desire to lead change in the village society there, broadened into something greater than activism at the village level – to the level of the relations between the two peoples in this land. Suddenly my dreams were breaking through boundaries and becoming ideologically more global, although they would not be easy to pursue on the practical plane. To live in a community that did not yet exist and create a reality that was yet to be, was more interesting than to confine my dreams to the reality as it already was. Bruno gently motivated me to feel his dreams as if they were my own. We talked a lot about dreams. He always said, "Dreams are ideas. And when a lot of people share the same ideas and the same dreams, there are good prospects that they will be realized."

* * *

Thus I began accepting Bruno’s invitations to weekend meetings. He called them "hilltop meetings." At first they were once a month. They had a religious-cultural character. On ordinary weekends, he conducted a Kabbalat Shabbat (greeting the Sabbath) ceremony on Friday evenings. On holiday weekends, there were special ceremonies to match. But all the ceremonies and rituals were for Jewish holidays only. Here and there, he did make adjustments to the text; on Passover, for example, the Haggadah was amended: He took out the sentence that read, "And You cast Your wrath over the goyim"; or when a prayer read, "He will bring peace upon us and upon all Israel," Bruno always said, "…and upon all the world."

I don’t remember his conducting any ceremony for a Christian or Muslim holiday. In those years, I did not view creating a balance among the three monotheistic religions as a necessity, nor did I think it important that we conduct Muslim or Christian holiday ceremonies. The argument then was between secularism versus religious devotion, rather than an interreligious dialogue, as the basis for the shared life we would be creating. I remember that in those days, Bruno would end the blessing over the bread with the text: Baruch ata adonai hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz, and Reuven would jump in and add his own interpretation: Baruch ata ha’amel hamotzi lechem min haaretz – Bruno blessed God for the bread, whereas Reuven blessed the laborer who sowed and reaped and baked it.

* * *

Despite my religious leanings, I was more supportive toward the non-religious ceremonies on the hill. Gradually, the majority began to share that outlook. After a while, when I came to know Bruno better, I began to see that it was very important to him to emphasize the Jewish component of his identity – as someone born to Jewish parents, although he had not received a Jewish education at home; and as someone who, paradoxically, became more aware of his Jewish identity only after joining the Church and becoming a believing Christian.

Bruno always made sure to emphasize that his Christian faith did not harm his Jewish identity, but the opposite. This was not an accepted idea in Israel. In his life, he worked very hard to emphasize that Christianity had its roots in Judaism, and he was very active in Jewish-Christian dialogue. When he decided to leave France and make his home in far-away Israel, he saw himself as a new immigrant just like all the Jewish new immigrants. He served in Israeli diplomatic roles to improve relations between Israel and the Catholic world. His highest attainment in this regard came at the Second Vatican Council, which ruled the Jewish people to be "not guilty" after all in the death of Jesus. Despite all of that activity, he was not able to find validation of his broader identity as a Christian Jew in the way that he wished. In my opinion, this is what drove him continually to emphasize his Jewish identity more, and his Christian identity less, in the society of Wahat al Salam / Neve Shalom.

Bruno was very sensitive about not mixing his activity and identity as a Christian with his work at Neve Shalom / Wahat al Salam, and particularly when communicating with the Israeli authorities. He was afraid to be accused of proselytizing, as other peace activists and humanitarian service activists had been accused in the past. Even in the beginning, he always explained, he tended to hold his meetings about Neve Shalom / Wahat al Salam outside any Christian setting. In my opinion, this was a very wise decision.

He prayed as a Christian, but privately: alone, or with other Christians, in his own modest room, or elsewhere – but not in the common room of the community on the hill, where Jewish rituals were conducted. He donned his priestly robes very rarely, and only for visits of senior Church dignitaries or when he went to visit Church figures on business for the community. He used to joke about this, saying, "This is a uniform that impresses the people I am going to see now."

* * *

When the first families came to the hill, Bruno declared many times that his role in the community as founder and leader was ended. He left the reins in the hands of the new dwellers on the hill. But he did not leave or withdraw, as so many others did who had been with him at the beginning. He and Anne Le Meignen, his companion and partner in the idea, remained with us – although both continued to live most of the week in Jerusalem, Bruno at Isaiah House and Anne at her own house. They visited the community frequently, and made time for educational work in the village – mainly in the spiritual context, which evolved into the foundation of the Pluralistic Spiritual Centre.

They also invested a lot of energy in public relations and fund raising. One of the big campaigns in the early years that I still recall was that Bruno approached every graduate of the college where he had studied engineering in Paris. He had obtained the addresses from the college, and wrote to these people about the idea of the community and asked every one of them to make a modest contribution equivalent to the cost of one meal – around $10. All the families who lived on the hill at that time sat together for several evenings in a row and folded all those letters together and put them in envelopes – about 15,000 of them, I think. The response was better than anticipated and a lot of money poured into the bank account in France.

Bruno traveled widely to give lectures. People loved his lectures. He spoke very simply about a grand and complicated idea, so that people who had little knowledge of the realities of life in the Middle East could identify with him and commit to helping him. Many of the longtime activists with the Friends associations became involved after being mesmerized by Bruno.

* * *

Bruno was someone who knew how to listen – an active listener. When I spoke with him, I felt not only that he was listening to me but that he was interested in having me continue. He showed that he was interested, asked open questions that encouraged me to say more and elaborate more. At our community meetings, when addressing a given question, he joined the discussion but did not rush to take a position. He made sure to hear everyone’s position and to understand them all. Because he tended to see differing ideas as different colorations rather than opposing ideas, his statements were encouraging; instead of saying "either this or that" as we did, he tended to speak in terms of "this way AND that way." Thus Bruno’s interventions were generally aimed at bridging or mediating between the various approaches of others. I don’t remember that he ever argued with people whose opinion differed with his own. Even if he took a position with a certain group, he always left room for other opinions, and would say to the other group, "Maybe you are right!"

He related in that same way to the conflict in the Middle East. He would explain his political position as: "The conflict is not between something right and something wrong, or a good side and a bad side, but rather a conflict between two right sides. There is no one absolute truth. Each side has its own truth. The only absolute truth is the—" (and he would say it in English) "’vertical dimension’"; and when we asked him what he meant, he would say: "God."

Bruno did not have an easy time at Wahat al Salam / Neve Shalom. In the early years, he sometimes felt despair because people were not joining the community and because financial support was so lacking. He told us that at times of despair he had sometimes thought about giving up the idea of a joint community, but before getting to that he decided at one point to give God an ultimatum: If in the next six months, two things did not happen to help develop the community, he would abandon the idea. After three months there were two positive signs: In 1977, a Jewish family came to live on the hill and, at the same time, a promise of financial support arrived from Europe.

Nor was it easy for him in the Church. Some attacked him and accused him of wasting his time with atheists, instead of providing religious services to the Christian community as was expected of him. It took some time until he was able to deal with these attacks. His response was appropriate for a visionary with an open mind. He would say to his critics, "It’s true that most of the people who have joined the village do not want to create a religious community, or have not yet found their way to God, but the work they do is certainly work that God expects will be done, and that is the most important thing."

* * *

I don’t feel comfortable talking about Bruno as if I’m describing him as more than human. When we talk about people who are no longer with us, or about leaders or heroes, we tend to recount not just the impressive sides of the person while ignoring their less impressive sides, but often to exaggerate our descriptions to match the hero-leader image. Bruno did not like to be above other people. His greatness was in his modesty. He did not hesitate to express lack of confidence and sometimes even confusion or helplessness. Bruno said of himself that he was not a very practical person, and when he offered an idea, he did not address the operational possibilities at all. He left implementation to God’s help. That is how he felt about his ultimatum to God: He felt that God had sent the first family and the first major financial support, while he discounted the many efforts and work invisted to raise money and to recruit that family. He wanted to remain the dreamer. He saw it as an important role. He always said, "If I had weighed things in practical terms, I would never have begun the project to found Neve Shalom / Wahat al Salam. I began the project even though most people thought it was impractical and even impossible."

Bruno, from the standpoint of ideas, never went into the details. What exactly would happen and precisely how things would be done did not interest him. He looked at things holistically and the important part was that there be a shared community of Arabs and Jews and that there be educational institutions in it. This goal could be approached along many paths. A lot of people did not understand this posture of Bruno’s. I myself,when I was all over the world talking about the community and its educational institutions, was often asked things like, "Is this what Bruno taught you?" Especially after Bruno’s death, many people expressed their concern about whether we were "carrying on Bruno’s way." They thought of him as a leader in the practical sense, which is something Bruno himself never wanted to be for this community.

Bruno believed fully in the people who joined the village, especially the first arrivals. He distinguished them with the term "havatikim" (the old-timers). He saw the reality of the village and its institutions as the complete fulfillment of his idea. He did not demand any special status in the decision-making process in the community. He participated like everyone else in the discussions, and his vote was just one vote among many. The only special status that he and Anne had was that they were accepted as members without having to live in the village full-time.

Bruno had three main projects in life that I know about. The first was to found a Church that would conduct the liturgy in Hebrew. The second was to create a center for Jewish studies for non-Jews (Isaiah House). And the third was Wahat al Salam / Neve Shalom. To the best of my knowledge, the only one of the three that succeeded in developing long-term and that remained after his death was Wahat al Salam / Neve Shalom. This fact is worthy of serious study and research to find out why.

Everything I’ve written here is about Bruno as I experienced him. This is not all of Bruno – it’s only my Bruno. I believe that others experienced Bruno in other ways, different than mine, and of course they have their own Bruno, who is also not the whole Bruno Hussar. Only Bruno Hussar himself could describe the whole Bruno.